•Four Uruguayan footballers have taken their own lives in the last six months

•FIFPRO spoke with Diego Scotti, president of MUFP, the country's professional footballers' union

•‘We aim to put tools in the hands of the footballers,’ he says.

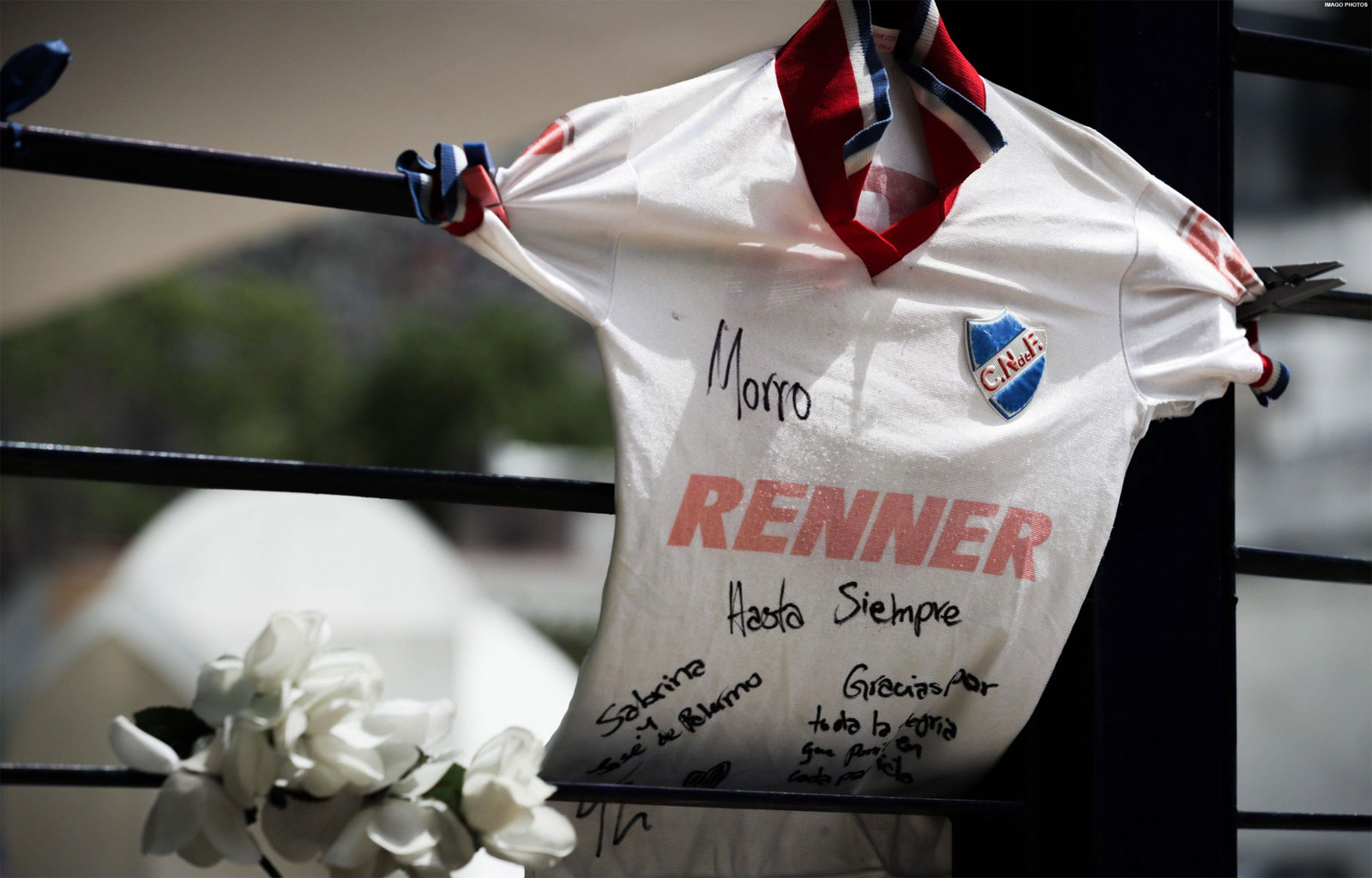

Uruguay's football community had not yet fully recovered from the suicide of Santiago ‘Morro’ Garcia in February when another blow was dealt on 17 July: Williams Martinez, a 38-year-old veteran defender who had become a historic symbol of his local league, playing for Villa Teresa in the second division, had also decided to take his own life.

Five days later there was yet another case. The country went from shock and dismay to consternation as Emiliano Cabrera, a 27-year-old player who played in the country’s interior leagues, also died of suicide. And last week, former player Maximiliano Castro (46) took his own life as well …

Four suicides in six months - how is it possible for four footballers from the same country to take their own lives during that timeframe? Away from the flashes of the Nacional-Peñarol classic in the knockout phase of the Copa Sudamericana, the focus of the Uruguayan football world has turned in recent weeks, for once, to its players’ mental health.

To contextualise what occurred, note that, in an initial analysis, what happened to García, Martínez, Cabrera and Castro is a response to a suicide crisis that Uruguay has been going through as a country for years.

According to data from the Ministry of Public Health, 718 people took their own lives in 2020. That translates into just over 20 suicides for every 100,000 inhabitants and one suicide for every 5,000 inhabitants. That is almost twice as high as the global average. In fact, during the previous year, more suicides were recorded in Uruguay than traffic fatalities.

‘Providing the footballers with tools’

Nevertheless, news of the fateful deaths of these four footballers elicited an almost obligatory reaction from those responsible for looking after their welfare during their careers.

MUFP president Diego Scotti said he was shocked and practically obliged to take action on this matter.

‘We feel extremely sad about what is happening. We are clearly aware that this is a social issue, so we are assuming our responsibility in order to address the issue from a different perspective and provide the footballers with tools,’ he said during an interview with FIFPRO.

Scotti, who played in Chile at the same time as Williams, said that MUFP has had an agreement for at least three years with the Uruguayan Society of Sports Psychology (SUPDE) providing a psychologist immediately for every player who requests professional help to treat a mental health issue. He also predicted that in the short term, the union will present a comprehensive project for mental health care and treatment.

‘Many players have contacted us in the last year. Some call, others come directly to our office. In those cases, one of our top priorities is to be able to ensure confidentiality concerning their request for help. Even their club managers should not be made aware of the situation,’ Scotti said.

The union president also indicated that in recent years, workshops and talks have focused on detecting mental health problems and encouraging players to talk about them.

Are you ready to talk?

The MUFP is one of the many player unions that joined FIFPRO’s global mental health campaign ‘Are you ready to talk?’ launched on 1 June last, although the coronavirus pandemic has delayed its implementation.

FIFPRO's global mental health campaign was the result of more than two years of field research to provide footballers with the tools to detect the signs of mental health disorders and to act on them through the appropriate pathways.

Alexandra Gómez, FIFPRO senior legal counsel and member of the project group, said, “Today there is still little awareness of this problem in football. The project, in its origins, had two main ideas: generate a referral network, so that in all those countries where a union is affiliated to FIFPRO, specialised personnel can be contacted to address these problems. And secondly, raise awareness among players and everyone involved in football.”

One of the main objectives for both Scotti and Gómez is that all clubs in Uruguay should have a sports psychologist on their coaching staff.

‘At the moment, very few teams in Uruguayan football have a psychologist in the locker room,’ Scotti said. ‘Conmebol has this as a requirement for clubs that appear in their competitions, but there are some clubs that will never play in international tournaments and still see the inclusion of a psychologist as an expense and not an investment,’ added Gómez.

Supported by the recent cases of elite sportswomen, Japanese tennis player Naomi Osaka and American gymnast Simone Biles, who went public with their mental health problems and put the brakes on their sporting activities, leaders of player unions are increasingly encouraging their members to step out of the shadows.